Exercise Guidelines

The government suggests that you exercise to maintain optimum health. Specifically, the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition recommends 75 – 150 (1 1/4- 2.5 hours) minutes of vigorous exercise or 150 – 300 (5 hours) minutes of moderate exercise per week. Or some combination thereof. Setting aside the wide range of the durations, you may find it challenging to adopt this advice unless you understand exercise intensity.

What is vigorous? What is moderate?

The words may mean different things to different people. The scientists who study this kind of thing ran into the same problem when coming up with these recommendations. Early research into the benefits of exercise was so positive that the researchers didn’t spend a lot of time quantifying it. When researchers wanted to explore the subject further, they needed a way to standardize the reporting of the intensity of physical activity so that they could compare activity levels across studies. If we are going to take the advice of the CDC and meet the physical activity guidelines, we have to know if what we are doing is vigorous or moderate.

METs as a measure of exercise intensity

A MET is a measure of the energy you expend sitting quietly. I say you because the unit is relative to your body. You may require more or less energy to sit still than the population average. For example, if you weigh 130 lbs and have 30% body fat, 1 MET will expend fewer calories than someone who is 200 lbs and 20%. This metabolic equivalent, also known as your resting metabolic rate, is the baseline against which various exercise intensities are measured. The rate at which a person expends energy, relative to the mass of that person: 3.5 mL of oxygen per kilogram per minute. There are many formulae for calculating the value of a MET that give roughly the same numbers:

An activity that uses 3 METs requires three times as much energy as you use sitting at rest. Likewise, an 8 MET activity uses eight times. Because a MET is a measure relative to your own resting metabolic rate, any given exercise activity should, in theory, require the same number of METs for anyone, male or female, large or small.

Let’s see how this idea applies to the exercise recommendations. The guidelines for physical activity define moderate as activities that require 3-5 METs and vigorous as >6 METs. In my article last week on Immersive VR Exergaming, I referenced a study that showed the Black Box Gym VR exergaming used a phenomenal 12.9 METs.

METs for some moderate activities:

| Moderate METS | Activity |

|---|---|

| 5.0 | unicycling |

| 4.0 | softball practice |

| 3.5 | walking 3.0 mph on a firm level surface |

METs for vigorous activities:

| Vigorous METS | Activity |

|---|---|

| 9.8 | running, 6 mph (10 min/mile) |

| 8.0 | ultimate frisbee |

| 7.3 | leisure tennis |

MET-minutes

The guidelines suggest a minimum of 75 minutes of vigorous activity or 150 minutes of moderate or some combination. What combinations will meet the minimum guidelines? You can answer that question with the help of the concept of MET-minutes. MET-minutes are equal to the number of minutes of activity times the number of METs that activity uses. The MET-minute target from the guidelines is between 500-1000 per week for optimal cardiovascular health. So, if you went on three 20-minute walks and practiced softball for an hour and a half, did you meet your weekly quota? Let’s do the math. For the walking, 3 x 20 = 60 minutes. 60 minutes x 3.5 METs = 210 MET-minutes. For the softball: 90 minutes x 4.0 METs = 360 MET-minutes. Add them together, and you have 570 MET-minutes. Congratulations, you made it!

How many METs is…?

How do you know how many METs a given activity requires? Lucky for us, there is the Compendium of Physical Activities. The Compendium lists the average METs for over 800 different physical activities across various domains, including sport, housework, occupations, and leisure. Compiled over the last 40 years from both published studies and expert opinion, the Compendium is a resource for researchers, software publishers, and non-specialists to understand the magnitude of physical activity.

Bill Haskell conceived the idea at Stanford University during the landmark Five City Project that tested the impact on cardiovascular health over a six-year health education intervention. When surveying subjects on their exercise habits, the researchers used questions about activities that had already been characterized by energy expenditure. In this way, they could accurately measure physical activity without hooking subjects up to a machine to measure their metabolic rate.

History of METs

The first Compendium was published in 1993 by Barbara E Ainsworth at ASU and a host of collaborators. Ainsworth et al. collected published data from various metabolic studies and coded it to specific activities. As researchers published more studies on the physical demands of diverse occupations and sports, they were added to the database. Her team updated in 2000 and 2011 to include new categories like exergaming and add more specific categories. Now Dr. Ainsworth is retired, but the Compendium is available online to anyone for any purpose. Dr. Stephen Hermann at Sanford Health in South Dakota maintains the Compendium.

Where does the data for METs come from?

The population averages for metabolic equivalents come from studies where they measured the amount of energy expended by measuring the amount of oxygen converted to CO2 across groups of test subjects. Other numbers came from expert opinions in cases where it is tough to directly measure human subjects, for example, swimming. The range of apparatuses used for these kinds of studies has changed over the years.

.

Metabolic Room

One way of measuring energy expenditure based on oxygen consumption was to put subjects in hermetically sealed rooms and measure the beginning and ending quantities of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the room. However, closed room studies were costly and tended to irk the subjects as they didn’t like staying in a sealed box.

Credit: Roomcalorimeters.com

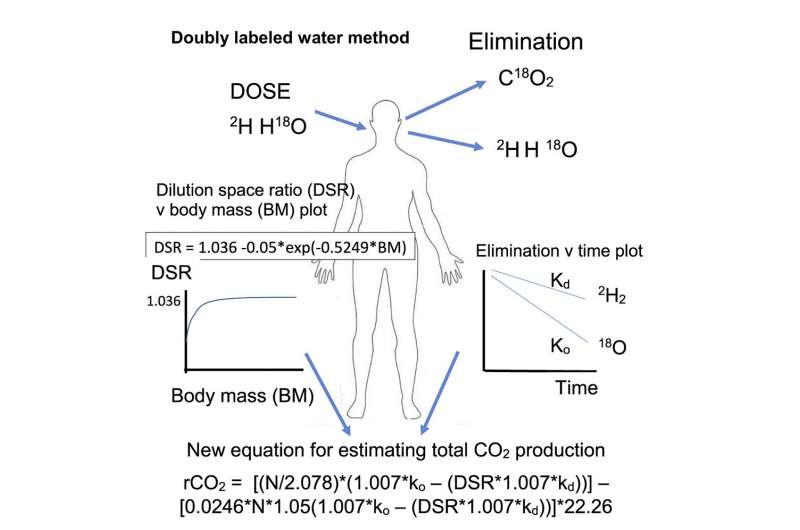

Doubly labeled water

The so-called “gold standard” for metabolic research is using doubly labeled water (DLW). In the DLW technique, subjects drink water continuing radioactive isotopes deuterium and oxygen 18. Urine samples are collected over the next two weeks, and the amount of each isotope is measured. The difference between the amounts of each isotope eliminated is the same as the amount of carbon dioxide expelled. Thus, researchers can calculate the energy expenditure from the amount of gas interchange. Unfortunately, the DLW and room techniques are complicated, expensive, and not so good at measuring a short-duration exercise.

Credit: Cell Reports Medicine (2021).

Metabolic Cart

in many recent studies, researchers use a metabolic cart to measure energy expenditure. The cart measures the amount of gas interchange between O2 and CO2, and researchers calculate energy expenditure. Carts are only really suitable for studies that take place in a lab as the equipment is delicate.

Credit: Cosmed

Portable metabolic analyzer

More recently, mobile shoulder and chest-worn metabolic packs allow researchers to measure gas interchange, heart rate, and temperature out in the field. The portable instruments allow investigators to capture data in an environment closer to the general public and have expanded the kinds of physical activities that can be characterized. Still, the portable devices aren’t waterproof, so the metabolic impacts of swimming have not been accurately measured.

Credit: PNOE

Published METs are averages

The METs for various activities are averages. Actual energy expenditure may be more or less depending on age, sex, body fat percentage, fitness, altitude, and other variables. Critics of the definition of MET suggest that among obese individuals, the standard formula overestimates energy consumption by 20-30%. The compendium website indicates a method to correct the published value of METs for specific individuals based on age, height, body mass, and sex.

Sex and METs

The Compendium is not the be-all and end-all. However, it is a valuable baseline for population averages. It also doesn’t have all the latest research. For example, the Compendium lists vigorous sexual activity as requiring only 2.8 METs. However, researchers Julie Frappier and Isabelle Toupin at the Department of Kinanthropology and Department of Sexologie, Université du Québec, found that sexytime takes a lot more energy than that. Their study measures vigorous sex at 6.0 METs for men and 5.8 for women. Clearly, the disparity between the sexes needs to be further explored.

You have to lift weights, too

Lastly, I have one final note about the guidelines for physical activity. In addition to that vigorous and moderate exercise, you have to pump some iron. Resistance training twice a week, whether bodyweight, resistance bands, or barbells, is part of the exercise RDA.