The Downside of fitness apps

Last year I worked out 161 times, ran 360 miles and set 22 personal records for running and biking. It didn’t take a lot of research to find any of this out. Fitness apps on my phone and GPS have made tracking these metrics easy. Having these numbers on hand has helped me improve my fitness. Peter Drucker said, “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.” What’s true for tech companies is true for managing your health. Technology makes it possible to measure so many aspects of your health: sleep, mood, nutrition, exercise, and more easily and more consistently. Having that data available to analyze allows you to manage your self-realization in very powerful ways. But the existence of your data and the uses others might make of it brings peril to ourselves and society. To protect yourself and everyone else, you need to think about fitness app data privacy.

Fitness Apps Track everything

I know I ran 6.5 miles this week because I tracked it in the Strava app on my iPhone. Strava records my location, speed, distance and pace for runs and rides on my bike. It also records my route using GPS. The record of that trip gets uploaded to a database of all the trips that its 30 million users have taken. To record a run, I don’t even need to have my Strava app open on my phone. I have a GPS watch that tracks the same metrics and automatically uploads them to Strava. I have another app, Fitbod which programs and records my weight-training. It also uploads to Strava. Each app talks to the others and they all talk to Apple health. I get a unified view of all my exercise and progress.

Measure to improve

Ever tried to lose weight? It is slow going. Any kind of sustainable effort yields gradual incremental results. Sustainable weight loss may be imperceptible from one day to the next. How about strength training? Once you get past the newbie gains, you may lift regularly for weeks without any apparent gain in strength. Fitness trackers help you to see the gradual progress over time. They help you see the pattern emerging, even if nothing seems to be happening daily. Being able to see this progress does wonders for one’s motivation.

The old way of timing runs

I used to track the times and pace of my runs before all the technology arrived. The process was laborious. On our weekend runs in Golden Gate Park, my wife and I would preview the route in our car. Hanging out the door of the slowly rolling Miata, we’d use the car’s odometer to mark off each kilometer of our 5K prospective route. We’d use stopwatches and notepads to keep time and calculate the pace on mile splits. Only the most dedicated of runners and metricians would go to the effort. Now, of course, millions of people all over the world use Strava to track their runs. They share data with their friends, and most people share it publicly as well. You can compete with and cheer on your friends. You can see how you rank out of all the people in the world on any particular route. It’s a worldwide community of runners.

Unintended consequences

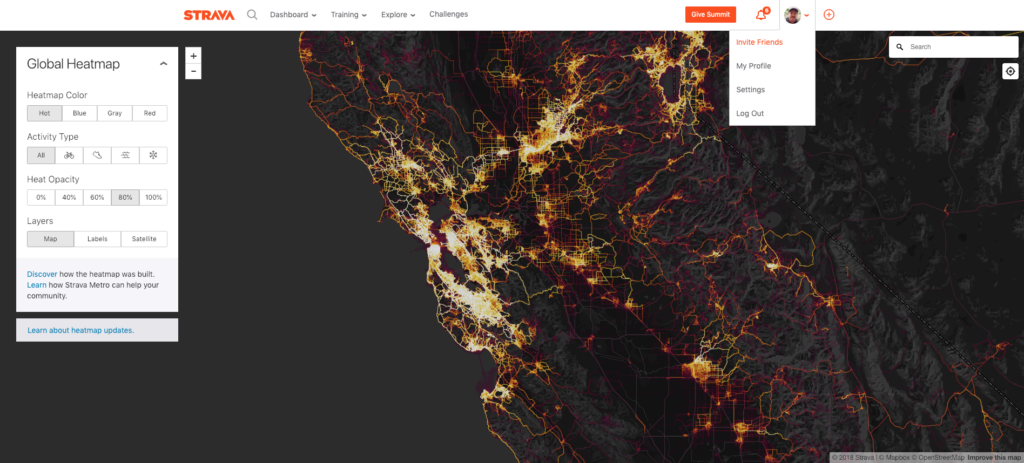

This dataset encompasses over 3 trillion GPS coordinates. Strava, wanting to demonstrate the richness of the data, transformed it into a zoomable global heatmap. The heatmap was a visual display of billions of routes, each a faint trace on top of each other superimposed on a world projection. Where many paths are stacked up, the color becomes more saturated. The most popular routes glow brightly, whereas the lonely trails barely show. A mesh of bright stripes covers Europe so densely you can hardly make out individual lines. In contrast, a large part of Somalia and Afghanistan are black voids.

Strava’s Global Heatmap

The project was stunning. Millions of people viewed it. I pored over the map to see where my runs had contributed to the whole. I looked for that one time I ran on an old country road in Normandy, where no one had ever run before. Some sharp-eyed person zoomed into a dark area of Afghanistan and saw traces way out in the middle of nowhere. Geometric trails like you would get if you were running around buildings and streets. It turned out that these routes were outlining military bases in Helmand province. Some special forces soldiers wanting to keep up their fitness were recording their runs, inadvertently giving away their base location. Now, this was not Strava’s intent in making this data available. It’s difficult to place blame on Strava or the operational security of the military. The fact is that the consequences of fitness data sharing aren’t always easy to anticipate.

Nutrition data is fitness data

For a year, I tracked everything I ate on MyFitnessPal. I would just start typing in the name of the food I’m eating, and the nutritional information pops up and gets logged. Whether it’s a burrito from chipotle or something you cooked up from a recipe at home, there is a record in the MFP database that has the calories, fat, protein, and carbohydrate content. If you can remember to do it once a day, logging your food takes less than 5 minutes. More than mere calorie counting, food logging apps let you focus on your nutrition with the same level of precision as a medical clinic or a sports training center. If recording your workouts was hard before smartphones, food logging was well nigh impossible. Now it’s trivial.

Food Tracking

In one year of food tracking, I lost 20 lbs. and put on 10 lbs. of muscle. I now eat better than I ever have in my life. I get the protein and fiber that my doctor has been nagging me about for years. And the benefits of tracking are sustained when you stop. The whole time I was logging food in MFP, I learned about the foods in my diet and how they contributed to my total calories and macronutrients. I was learning. After a year, I was pretty much done with MFP. I could tell at a glance how many calories were in a dish and what I needed to eat to hit my macronutrient targets. I could also see some patterns that weren’t obvious before. For example, if I ate more than the RDA of sodium any particular day, my weight would go up by several pounds the next. That sodium in my system was helping me retain water. I learned not to freak about large weight fluctuations and focus on long-term trends.

Insurance companies put the fitness data to use

Some researchers think that putting so much attention on what you eat might lead to disordered eating. A logical premise, but the research so far doesn’t back that up. The danger doesn’t come from how you use the data but from how others might make use of it. Insurance companies have started to look at social media feeds to help evaluate risk in insuring people. Aetna’s CarePass service already has explicit partnerships with MyFitnessPal, Fitbit, RunKeeper, and Withings. It’s unclear what fitness data privacy constraints are explicit terms of those deals.

Right now, CarePass is incorporating the data into corporate wellness programs. The urge to use that fitness data for individual health insurance decisions will be hard for corporate insurers to resist. But if Aetna starts pricing healthcare premiums based on how many steps you take a day, we will have to consider the consequences of that data-sharing. Update: CarePass failed. One of the suspected reasons is that consumers do not trust their health plans with their self-tracking data.

Fitness Data is Not so anonymous

Consumer backlash has started to make companies pay more attention to privacy concerns. Anticipating the privacy protections making their way through legislatures, many companies have added settings to make your data private. Most want to keep access to the aggregate data and keep anonymized records. But anonymity may not perfectly obscure your identity. Studies have shown that over 80% of people can be identified with just three pieces of information: their birth date, gender, and zip code.

Given the amount of additional location information that is available from fitness and food trackers, it’s hard to imagine how that percentage wouldn’t go up with the health data and powerful machine learning technologies to mine it. So it’s likely despite your best efforts to obscure it, your health and fitness data will become known. And this is incredibly valuable to the companies that profit from your health or lack thereof.

Fitness data and AI

It becomes even more valuable when combined with all the other data that is collected about you. Imagine adding this kind of data to the information from your grocery store loyalty card. An insurer or an employer can use this information to make all kinds of decisions that affect your welfare. If you have diabetes, for example, and your fitness tracker shows that you only take one half-hour walk a week but buy a pound cake every other day, your insurer is going to want to figure out how to raise your rates to account for the increased risk of illness. You may think that that is fine. Why shouldn’t people should be rewarded for their healthy habits? What’s wrong with giving people an incentive to eat well and exercise?

Sloppy data

The problem is the lack of quality control in the datasets. First off, I don’t track every workout. Sometimes I just like to run in the park without any technology at all. Second, anyone analyzing my Safeway rewards card data would get the wrong idea about what I eat. I don’t buy all my groceries at Safeway. If you just looked at Safeway data, you’d think all I was eating was pork and club soda. I buy most of my food at a greengrocer down the street, where I pay in cash. Nobody’s tracking those purchases. If they were, that analyst might be concerned about the overabundance of kale and root vegetables in my family’s diet. And we shop at Trader Joe’s, Costco, and the local bakery too.

Mistaken identity at the grocery store

The point is moot for me because I use somebody else’s club card code at Safeway. I had initially signed up using my cell phone number ten years ago. When I switched numbers, somebody else got my old number, and my club card went with them. All my purchases appear on that account. The name has been updated either automatically by pulling from the phone company database or because that phone number’s new owner signed up with Safeway. Either way, Mrs. Rodriguez is probably getting a few cookie coupons that are rightfully mine. I can live with it.

Protect yourself and your Fitness data

There are three things you have to do to protect yourself. 1.) Read the data use and privacy policies of any apps you use. Weigh whether there are tangible advantages of sharing your information. Decide if they are worth the risk. 2.) Resist. Don’t make it easy to collect and aggregate your data. Never use your name or personally identifiable information in your usernames. 3.) Get involved. Decisions about your data privacy are being debated in hearing rooms and public fora right now. Support organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation are advocating for your rights as a consumer. Become an advocate yourself.